The Subtle Art of Propaganda

The oft quoted and paraphrased saying “the first casualty of war is truth” has been attributed to Warren Hiram Johnson, an isolationist Republican Senator who used it in a speech in 1917, the year that America entered the First World War. His actual words were, “the first casualty when war comes is truth.” He quite possibly drew his inspiration from his more famous namesake, the British author, Samuel Johnson, who in 1758, wrote that “'among the calamities of war may be jointly numbered the diminution of the love of truth, by the falsehoods which interest dictates and credulity encourages.” Whatever its provenance, it is one of those phrases that becomes detached from its source by virtue of its terse, blunt and acute veracity, mirroring that other phrase, “the fog of war” coined by Carl von Clausewitz, which refers more specifically to the difficult and uncertain conditions on the battlefield that make clear decision-making challenging. As with Johnson’s original speech, von Clausewitz’s actual words were modified, the original excerpt from his 1832 text (On War) being

“War is the realm of uncertainty; three quarters of the factors on which action in war is based are wrapped in a fog of greater or lesser uncertainty. A sensitive and discriminating judgment is called for; a skilled intelligence to scent out the truth.”

Taken together, the deleterious effect of war on the human ability to grasp the truth and grapple with uncertainty leads, on the one hand, to the degradation of truth itself (being the first casualty) and, on the other, obscuring the truth to such an extent that only a ‘sensitive and discriminating judgement’ can scent it out. The normal conditions under which logic and reason can function are thus disrupted, necessitating a more perspicacious acuity that operates like a sniffer dog, catching the scent and doggedly pursuing it while the field is filled with the fog and filthy air in which fair is foul and foul is fair. If war is hell, a phrase attributed to Union General William Sherman, who witnessed his fair share of foulness in the American Civil War, the worst effects are visited on those who experience it directly, be it the soldier, the civilian, or the innocent bystander caught in the crossfire. But for those who witness, report, document and record the causes, consequences and outcomes of war, the risk is relative to their proximity to the battlefield, on their ability to make sense of what is happening and at the same time be of sound mind and judgement to relay the account accurately, impartially and comprehensively, avoiding any bias and political motivation, other than to tell the truth. Naturally, there are significant impediments to this goal, notwithstanding the fog of war itself but also the interference that comes with the territory, be it the danger of being killed, advertently or inadvertently, the imposition of restrictions on reporting, media blackouts or, more egregiously, of bias and intervention from the media itself. Indeed the role of the media in influencing the direction or outcome of a war can take various forms, from patriotic one-sidedness to blatant censorship, editorial manipulation and, in certain cases, drumming up ‘war fever’ to foment and initiate conflict. This is where journalism, theoretically the telling of truth through facts and evidence, becomes blurred by propaganda, the obscuring of truth through exaggeration, invention, falsehood and the emotional manipulation of the masses. Today, it is almost impossible to separate the news from propaganda, not because there is no difference between them, but because the one has been influenced and corrupted by the other to such an extent that what passes for journalism is often propaganda through the back door.

Propaganda arguably predates journalism depending on how we define it. While Thucydides’ History of the Peloponnesian War is considered as one of the first works of history, it has also been described by modern historians as an early form of journalism and certainly not one that can be relied upon to provide an objective account of the war. It is also written from the Athenian perspective, despite the author’s professed motivation to be neutral and not for the “taste of an immediate public.” It is nonetheless a work that has stood the test of time and set a certain precedent for historical writing that, in contrast to Herodotus, shifts the dial beyond hearsay, mythology and supposition. Thucydides is a war correspondent conscious of the vicissitudes of the battlefield, mindful of the difference between myth and facts and seeking to tell the truth, albeit with the limited resources of the time. By contrast propaganda has little use for facts other than those which can be weaponised to achieve a certain end, be it benevolent or malevolent or both. It would be incorrect to assume that all forms of propaganda are inherently belligerent. Etymologically linked to the word ‘propagate’, the term first occurs in the Catholic Church as a medium for spreading the Gospel, specifically as it relates to missionary work. Clearly the intentions of the church in converting and controlling native populations was highly questionable and that organised religion, for all its benevolent intentions, is deeply and darkly entwined with politics, imperialism, injustice, war and genocide. Where the sword goes, the pen surely follows and sometimes the reverse is true.

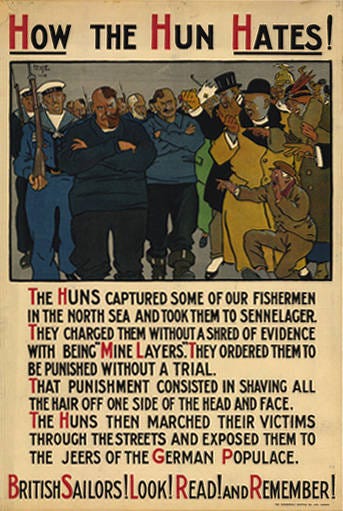

It could certainly be argued that propaganda in the modern sense closely resembles the dogmatism of religion in that it seeks to impose authority over a group, community, or nation through persuasion, which can manifest itself as enlightenment or obscurantism, resistance or despotism, liberation or bondage. In all cases, the truth is either diluted or veiled behind an ulterior motive that invariably coincides with power. The pen may be mightier than the sword in literary terms, but politically it is either pitted against power or completely aligned with it. Language is an extremely persuasive and powerful tool in the hands of those who want to galvanise and unify a movement because as the Bible states, in the beginning was the word and that word was God, or in the original Greek, the Logos, which is the spirit of the word as a logical and believable truth. How that truth is articulated, positioned, communicated and proselytised is the essence of how a sect can become a world religion, a creed the voice of a people, and an ideology the bulwark of a national community. When Marx wrote the Communist Manifesto, the intent was not, as in Das Kapital, to dissect the immoralities of capitalism, but to codify a call to arms and inspire the working class to revolt. Lenin and Trotsky took this call much further, consciously and deliberately employing propaganda to create a vanguard that would not simply react to the discontent of the oppressed but to lead them, like Moses, out of the wilderness and into the promised land. The masses could not be relied upon to liberate themselves. If anything they were too distracted and apathetic to do it alone. Propaganda, or agitprop as the Soviets called it, shrewdly combining propaganda with agitation, was not simply a device to augment the struggle of the proletariat. It was instrumental and vital to the revolution, without which the cause was vulnerable to dilution, compromise, apathy and, moreover, by the counter-offensive of those reactionary forces that developed a propaganda of their own. Hitler confessed that he learnt more from the Socialists and Communists than any other movement how to use propaganda to effectively target his enemies. Yet it was not just the extremists that had shaped and exploited the populace to achieve their aims. The British in the First World War used the notorious image of The Hun to demonise the Germans in the same way as the Germans would later dehumanise Slavs, Jews and others to justify extermination and genocide. Despite all the attempts by the United Nations to prevent such crimes from being repeated, the historical record is grim and continues to be so. There is not a single society that is immune to the power of propaganda, whether consciously or subliminally, which may speak to a congenital propensity that each person has to be at one time or another the victim or the exponent of propaganda in some form. A few examples will suffice to illustrate this.

Prior to the Spanish-American war in Cuba, the media mogul and chief editor of the New York Journal, William Randolph Hearst, circulated heavily embellished stories of Spanish atrocities to incite war fever, directly influencing President McKinley’s decision to intervene militarily.

Prior to the First Gulf War, western media outlets reported fake accounts of Iraqi soldiers overturning and destroying incubators in a Kuwaiti hospital, sparking public outrage and indignation.

Prior to the Second Gulf War, Secretary of State Colin Powell declared before the United Nations general assembly that Saddam Hussein was collaborating with Al Qaeda to obtain materials to build a nuclear bomb. (Powell was well aware that this was untrue at the time and later admitted this to be the case).

Following a miscarriage, the American Puritan dissident, Mary Dyer, became along with her followers the victim of a smear campaign by Massachusetts Governor, John Winthrop, who described her stillborn child as a monster and its mother as a bearer of monsters, precipitating what later became the witch craze in Salem.

Following the October 7th attacks on Israel by Hamas, Israeli media circulated stories of beheadings, torture, mass rapes and infanticide to augment Israel’s brutal war of retaliation and subsequent genocide. The claims have been proven to be wildly exaggerated and largely false.

In 2016, QAnon disciple, Edgar Maddison Welch, opened fire inside a pizza restaurant in North Carolina convinced that the premises was harbouring sex-slaves linked to a paedophile cult that included Hilary Clinton and other high-profile Democrats. (Had Welch alighted on Epstein Island, he may have had more traction in court).

There are thousands of examples of how propaganda is one of the most powerful and effective ways to persuade, manipulate, brainwash and incite individuals and whole communities to accept, passively or actively, what their masters disseminate across multifarious media. One does not have to be an extremist or a fanatic to be swayed or convinced that the message is bona fide, even where the level of exaggeration and embellishment is obvious. In some cases, their may be a grain of truth to the message itself, making it all the more compelling and believable but it is not imperative for there to be any credible basis to the lie. As Nietzsche wrote, “he who does not deceive does not know the truth”, meaning that in a philosophical and psychological sense, we are all liars who know how to manipulate truth. Deception under certain circumstances may even have an ethical component to the extent that a lie used to defeat a greater lie or a greater evil can be justified. Conversely, a lie may be so effective in masquerading as truth that it can condition a people for decades if not centuries, especially if compounded by fear, censorship and the use of force. Turning citizens into their own policeman, if not their own executioners, is a state of mind that can infect a population as ancient as the Aztecs and as contemporary as Mao’s China. It doesn’t mean that such societies are permanently under a toxic spell, but that their motivations, passions and sometimes their very survival relies on a certain degree of acquiescence to those that control them. We have never been and we may never be immune to such propensities because the circumstances under which we can be manipulated and controlled shapeshift from era to era, becoming either more subtle and sophisticated as in the case of Artificial Intelligence, or alternately more overt and barbarous as in the case of ISIS. Civilisation and barbarism are by no means at opposite ends of the spectrum. The more a society believes or is persuaded to believe it is superior, morally or culturally, the more it is willing to barbarise and dehumanise those it considers its inferiors. Israel vindicates its genocide not simply through vengeance but through righteous indignation, in turn becoming more barbarous and brutal than its enemy.

In 1938, Orson Welles delivered a radio broadcast based on HG Wells’ novel War of the Worlds. Using sound effects and astronomical references, Wells’ performance provoked a visceral reaction from his listeners, many of whom believed that the earth was under attack. With reports of car accidents, suicides, and people barricading themselves in their homes, the level of mass hysteria proved that even a work of fiction, if provocative enough and piped through the airwaves could go viral at a time when radio was becoming the most popular and compelling medium. Psychologically the incident can be explained by the fact that war was breaking out in Europe, thus exaggerating an existing trepidation, but there is no reason to believe that it could not have occurred at a more peaceful time. And to assume that we are nowhere near as gullible as those naïve listeners whose early exposure to mass manipulation made them dupes of a mellifluously manipulative genius in Wells, we would do well to remember just how easily the propaganda of our times can morph into seemingly credible sources of reportage, when facts and alternative facts coexist, meld and contort the multidimensional prism where truth, lies, opinion, collusion and delusion twist our senses into an acute state of mental dysmorphia in which the algorithms that reinforce bias in turn bias our capacity to distinguish between fact and fiction, truth and propaganda, reality and what passes for reality.